What Is The Size Of The Labor Force?

| | The neutrality of this commodity is questioned because it may testify systemic bias. In particular, in that location may exist a strong bias in favor of Women. (Feb 2021) |

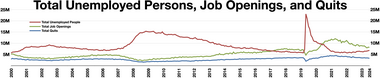

Total job openings

Quits charge per unit

Employment trends in key variables indexed to bear witness relative changes in the number of persons (starting point = 100). For instance, from June 2009 (the official cease of the Great Recession) to July 2018, the number of persons not in the labor strength increased past eighteen% as millions of Baby Boomers retire, just the labor force increased 5%.

The labor strength is the actual number of people available for work and is the sum of the employed and the unemployed. The U.S. labor force reached a loftier of 164.6 million persons in Feb 2020, just at the starting time of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.s.a..[1] The U.S. labor forcefulness has risen each twelvemonth since 1960, with the exception of the menstruation following the Slap-up Recession, when it remained below 2008 levels from 2009 to 2011.[1] In 2021, The Slap-up Resignation resulted in record numbers in voluntary turn over for American workers.

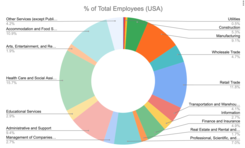

United states Census Bureau Employment (NAICS/SIC)

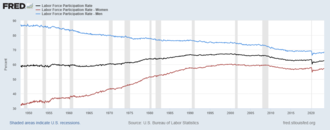

The labor force participation rate, LFPR (or economic activity rate, EAR), is the ratio betwixt the labor forcefulness and the overall size of their cohort (national population of the aforementioned historic period range). Much as in other countries in the Due west, the labor force participation charge per unit in the U.S. increased significantly during the afterward half of the 20th century, largely because of women entering the workplace in increasing numbers. Labor strength participation has declined steadily since 2000, primarily considering of the aging and retirement of the Baby Smash generation. Analyzing labor force participation trends in the prime working age (25-54) cohort helps split the impact of an aging population from other demographic factors (e.g., gender, race, and education) and authorities policies. The Congressional Budget Office explained in 2018 that higher educational attainment is correlated with higher labor forcefulness participation for workers anile 25–54. Prime number-aged men tend to exist out of the labor forcefulness because of disability, while a central reason for women is caring for family unit members.[ii]

Definition [edit]

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines the labor force as:[3]

Included are persons xvi years of age and older residing in the 50 States and the Commune of Columbia who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities, homes for the aged), and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces.

Gender and the U.Due south. labor force [edit]

United states of america labor force participation rate from 1948 to 2021, by gender.

Male participation

Total labor force participation

Female participation

Women [edit]

In the United States, at that place were three significant stages of women's increased participation in the labor force. During the late 19th century through the 1920s, very few women were employed. Working women were often immature unmarried women who typically withdrew from labor force at matrimony unless their family needed two incomes. These women worked primarily in the textile manufacturing industry or as domestic workers. This profession empowered women and immune them to earn a living wage. At times, they were a financial help to their families.

Between 1930 and 1950, female person labor force participation increased primarily due to the increased demand for office workers, women participating in the loftier school move, and electrification which reduced the time spent on household chores. In the 1950s to the 1970s, nearly women were secondary earners working mainly every bit secretaries, teachers, nurses, and librarians (pink-neckband jobs).

Claudia Goldin and others, specifically point out that by the mid-1970s there was a flow of revolution of women in the labor forcefulness brought on by unlike factors. Women more accurately planned for their future in the work forcefulness, choosing more than applicative majors in higher that prepared them to enter and compete in the labor market. In the Us, the labor force participation charge per unit rose from approximately 59% in 1948 to 66% in 2005,[four] with participation among women ascent from 32% to 59%[5] and participation among men declining from 87% to 73%.[6] [7]

A mutual theory in modern economics claims that the rise of women participating in the U.s.a. labor strength in the late 1960s was due to the introduction of a new contraceptive technology, birth control pills, and the adjustment of historic period of majority laws. The use of nativity control gave women the flexibility of opting to invest and advance their career while maintaining a relationship. Past having control over the timing of their fertility, they were not running a risk of thwarting their career choices. Yet, only 40% of the population actually used the birth control pill. This implies that other factors may accept contributed to women choosing to invest in advancing their careers.

Another factor that may have contributed to the trend was the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex. Such legislation diminished sexual bigotry and encouraged more than women to enter the labor market place past receiving fair remuneration to help raise children.

Historical trends [edit]

Co-ordinate to the US Census in 1861, ane third of women were in the labor force and of these one quaternary were married women.[8]

Co-ordinate to Ellen DuBoise and Lynn Dumenil, they estimate that the number of women in the labor force from 1800 - 1900 are:[9]

| By Yr | % Women in Labor strength | Women equally % of Total Labor Strength |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 4.6% | 4.6% |

| 1810 | 7.9% | 9.4% |

| 1820 | half-dozen.ii% | 7.3% |

| 1830 | 6.four% | seven.4% |

| 1840 | eight.4% | nine.6% |

| 1850 | ten.i% | 10.8% |

| 1860 | nine.7% | ten.2% |

| 1870 | 13.7% | xiv.8% |

| 1880 | 14.7% | 15.ii% |

| 1890 | 18.2% | 17.0% |

| 1900 | 21.2% | 18.ane% |

According to the Usa Section of Labor, as of 2017 women make up 47% of the full labor force with 70% of them mothers with children nether 18 years of age.[10]

Men [edit]

Men's labor force participation has been falling consistently since at to the lowest degree the 1960s.[11] This applies to both the overall and prime working historic period (25-54), as discussed in the analysis section beneath.

Race and the U.S. Labor Strength [edit]

Occupation [edit]

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of 2019 Asians are near likely to hold a management position, while Hispanics or Latinos are well-nigh likely to concord a job in the service sector.[12]

| Race | Production, transportation, and cloth moving | Natural resources, construction, and maintenance | Sales and office | Service | Management, professional person, and related |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 11.iii | 10.i | 21.3 | 15.nine | 41.4 |

| Blackness or African American | 16.2 | v.vii | 22.3 | 23.eight | 31.9 |

| Asian | 9.one | 3.ane | 17 | 15.8 | 55 |

| Hispanic or Latino | xv.4 | xvi.iv | twenty.6 | 24.2 | 23.3 |

Health Inequalities in the Labor Force [edit]

A person's occupation is 1 of the master social determinants of health which greatly contributes to health inequalities and health disparities, racially and ethnically.[14] [xv] Determinants under the occupation category include: income, housing, paid sick leave and wellness insurance; they are related to a person's socioeconomic status.[16] [17] The U.Southward. health intendance arrangement is continued to employment and it is very likely that a worker is paying for health insurance through their employer; low-wage workers who opt for coverage through their employment pay a college portion from their income than their heart- income and college- income counterparts.[18] There is a disproportionate number of employed workers, based on race across the labor sectors, particularly those of loftier- risk.[19]

| Race | Educational, Wellness & Social Services | Arts, Entertainment, Recreation, Accommodation & Nutrient Services | Retail Merchandise | Transportation, Warehousing & Utilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 7.five million | 4.ii meg | 7 meg | 4.one meg |

| Black/ African American | 1.four meg | 871,000 | 1.3 million | 658,000 |

| Asian | 738,000 | 435,000 | 495,000 | 133,000 |

*Numbers in the tabular array are estimated.

During COVID-19 [edit]

The Family Showtime Coronavirus Act (FFCRA), provided mandated paid ill leave for workers that are impacted by COVID-xix and people of color are afflicted since because of the exemptions in that law; simply sure public employers, private employers of less than 500 employees, and small business concern with less than 50 employees may qualify for the mandate.[24] [25] COVID-nineteen affected workers disproportionately, with Black and non-White races more likely to make upward the baseline of the essential workforce this exposes to them to infections causing them to exist unable to or to go along to work; FFCRA (2020) was passed in hopes of protecting workers simply the ambivalence of the constabulary puts minorities' paid sick leave at gamble.[24] Less than thirty% of the workforce in the United States have paid ill get out that is protected by state law[26]

Analyzing the labor force participation rate [edit]

The line nautical chart shows the long-term decline in labor force participation for U.S. males of prime-working age (25–54 years), based on educational attainment.[27]

Overall rate [edit]

From 1962 to 1999, women entering the U.S. workforce represented a about viii per centum point increase in the overall LFPR.[28] The U.S. overall LFPR (historic period 16+) has been falling since its all-time loftier betoken of 67.3% reached in January–April 2000, reaching 62.vii% by January 2018.[29] This turn down since 2000 is primarily driven by the retirement of the Infant Nail generation. Since the overall labor force is defined equally those age 16+, an aging lodge with more persons past the typical prime working historic period (25-54) exerts a steady downward influence on the LFPR. The reject was forecast by economists and demographers going back into the 1990s, if not earlier. For example, during 1999 the BLS forecast that the overall LFPR would exist 66.9% in 2015 and 63.2% in 2025.[30] A 2006 forecast by Federal Reserve economists (i.e., before the Groovy Recession that began in December 2007) estimated the LFPR would exist beneath 64% past 2016, close to the 62.7% average that year.[31]

The labor forcefulness participation rate decreases when the percentage increase in the defined population (denominator) is greater than the per centum increment in the labor force (i.e., the sum of employed and unemployed, the numerator). With respect to the unemployment rate, if the per centum increase in the number of unemployed (numerator) is greater than the percentage increment in the number in the labor forcefulness (denominator), the unemployment charge per unit volition rise.[32]

Prime working age rate [edit]

Economists also analyze the LFPR for those prime-aged workers, aged 25–54. Mathematically, this ratio is computed with a numerator (labor strength age 25–54) and denominator (civilian population age 25–54). This tin assistance remove the touch on of aging demographics, to better understand trends among working-anile persons. The prime-anile LFPR peaked at 84.five% at three times betwixt October 1997 and April 2000. Prior to the Groovy Recession, the rate was 83.3% in November 2007, then fell to a trough of fourscore.5% in July 2015, before steadily climbing back to 81.7% in January 2018.[33] Information technology is one of the few cardinal labor market variables that had yet to recover its pre-crisis level as of Jan 2018 and is an indicator of slack in the labor market.[34]

- Men's prime number-aged labor strength participation has been falling consistently since at least the 1960s. It ranged betwixt 93 and 95% during the 1980s, fell to around ninety% during the 2000s and was 88.5% in Oct 2017.[35] Higher labor force participation is correlated with higher educational attainment.

- Women's prime-anile labor force participation rose consistently from at least the early 1960s, reaching a peak of 77.2% in August 1997. It has fluctuated around 75% since then, resisting the decline in men's prime number age participation.[36] Women have increased their educational attainment relative to men.

The Congressional Budget Function explained in 2018 higher educational attainment is correlated with higher labor force participation. Prime-aged men tend to be out of the labor force due to disability, while a fundamental reason for women is caring for family members. To the extent an aging population requires the aid of prime-anile family members at home, this also presents a down pressure on this cohort's participation.[2]

Teen labor forcefulness participation [edit]

In 1979, at that place had been the highest teen labor strength participation charge per unit with 57.9 percentage of teens participating.[37] In the early 21st century, there had been a drastic decrease in the teen labor forcefulness participation charge per unit with the decrease expected to only decline more from 2017 to 2024.[37]

The reason for the subtract in teen labor forcefulness participation was the environment teens were in, including pressures by their family.[37] The environment pressured many to become to higher, summer school became more prevalent, and schoolwork became more exhausting.[37] The price of college has risen over the years, merely it has not persuaded teens non to become to higher. There is a college number of teens requesting help to nourish higher.[37] There is an increased number of teens attending school and a decreased number of teens participating in the labor force.[37]

Teens who do not desire to attend college take competition from individuals that are more experienced such equally individuals who have graduated from college with a degree, individuals that are adults, and individuals from other countries that movement to the Usa and try to obtain jobs.[37] This has also contributed to the decrease in teen labor force participation.[37]

According to a Pew Research Middle assay on monthly 1944-2017 Current Population Survey, Millennials aged more than 16 represented the largest generation in the U.Southward. labour force and the highest quote since the postwar, with more than 35% of participants working or looking for a piece of work.[38]

Participation during COVID-19 [edit]

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a massive driblet in employees persons in the labor force. According to Pew Research Middle, from February 2020 to February 2021 an estimated 4.two million people left the labor forcefulness considering of COVID-19, a loss of employment that far exceeds that seen during the Great Recession.[39] Out of those that left the labor force, women accounted for 2.iv 1000000, which is more than one-half of those that left despite the fact that they business relationship for less than half of the labor force.[39]

The Great Resignation [edit]

The pandemic created a shift in the labor market where workers began voluntarily leaving their jobs in large numbers. The U.Due south. Bureau of Labor Statistics states by July 2021 iv meg workers had voluntarily separated from their employer.[40] A number of factors were impacting the trend which started in early 2021. With the large shift to working from home, and the risks associated with returning to unsafe working conditions, lack of childcare, coupled with a labor market where i tin leave a job and higher pay elsewhere, and overall employee burnout, employers were experiencing higher turnover rates with petty evidence of slowdown.[41] According to the U.Southward. Bedchamber of Commerce, all industries in the U.Due south. labor market were impacted with highest numbers in hospitality and healthcare, while structure, mining, and oil/gas industries saw picayune to no impact.[42]

A SHRM survey found that Millennials and Gen Z have a higher probably to look for new work than Baby Boomers and Gen X. The findings cite a desire to seek employment that will allow them to alive a more counterbalanced life, and having access to growth opportunities lacking in their electric current roles, for the workforce exodus of their respondents.[43] These reasons are not isolated to the SHRM respondents, all the same. A shift in worker attitudes, overall priorities, and perception of their relationship with their jobs is a symptom of the pandemic, which forced many to drastically change the style they work and live.[ citation needed ]

The shifting sentiment of workers during a time of instability, women'south rate of exit were twice that of men, co-ordinate to Texas A&M University Organizational Psychologist, Anthony Klotz,[44] who besides coined the term "The Great Resignation." As a event, their participation in the labor force is at a 30 twelvemonth low.[45]

Foreign-born workers [edit]

There were 27.8 one thousand thousand foreign-built-in workers in the labor force as of January 2018.[46] This group had an overall LFPR of 65.1% in January 2018.[47] As of 2013, the highest grouping of people participating in the Foreign-born immigrant labor forcefulness in the U.s. were individuals from Mexico and Fundamental America.[48] They made upwardly of 40.3 percent of the immigrant labor force participation.[48] Mexico heavily outweighed Cardinal America in which they held the majority of workers with 32 percentage of workers just from Mexico.[48] In 2013, California held most of the foreign-built-in worker immigrants in the The states, with about one-half from Mexico and Central America.[48]

Foreign-born women [edit]

Since 1960, foreign-built-in immigrant women have the lowest labor market participation rate between all of the groups in the United States.[49] The groups include immigrant men and individuals born in the U.s..[49] Foreign-built-in immigrant women participate in the labor forcefulness between 75 and 78 percentage lower than native built-in males.[49] In terms of labor forcefulness participation, the foreign-born immigrant women from Mexico and Central America are the smallest number of participants in the labor force.[48] As far as foreign-born immigrants that are trying to participate in the labor forcefulness merely cannot find employment, the unemployment rates are as follows. The unemployment are foreign-born immigrant women workers (9.1 percent), native women workers (7.9 percent), Mexico and Primal American strange-built-in immigrant women workers (12.1 percent), and other foreign-born immigrant women workers (7.7 per centum).[48]

Foreign-born men [edit]

In terms of labor strength participation, the foreign-built-in immigrant men from Mexico and Key America are the largest number of participants in the labor force.[48] The number of potential labor force participants for foreign-born immigrant men are foreign-built-in immigrant men workers (9.9 percent), native men workers (10.4 pct), Mexico and Central American foreign-born immigrant men workers (11.iv percentage), and other foreign-born immigrant men workers (viii.6 percent).[48] Strange-built-in immigrant men have a similar unemployment rate to native workers, but the unemployment rate for foreign-born immigrant men that are from Mexico and Cardinal America is considerably more than other groups of strange-built-in immigrant men looking for work in the United States.[48]

International comparison [edit]

For 2017, the Central Intelligence Bureau ranked the U.Due south. as having the quaternary largest labor force in the earth at almost 160 million, behind Prc (807 meg), Bharat (522 million), and the Eu (235 one thousand thousand).[l]

Come across also [edit]

- Unemployment in the United States

- Workforce

- Unemployment

- Employment-to-population ratio

- Listing of countries by labor forcefulness

- Proletariat

- Feminization of poverty

Further reading [edit]

- Abraham, Katharine G., and Melissa Southward. Kearney. 2020. "Explaining the Decline in the Usa Employment-to-Population Ratio: A Review of the Bear witness." Journal of Economic Literature, 58 (3): 585–643.

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Civilian Labor Strength". FRED. January 1948. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ a b CBO-Factors Affecting the Labor Force Participation of People Ages 25 to 54-Feb seven, 2018

- ^ "BLS Glossary". Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Bureau of Labor Statistics Data". Retrieved fifteen Oct 2014.

- ^ "Bureau of Labor Statistics Data". Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Breaking down the male person participation rate by age subclass shows a marked decline in participation among men 55 and over from approximately 71% in 1948 to 44% in 2005 [ane]. Amongst younger historic period groups a reject is noticeable, only not about as desperate.[2]

- ^ "8=2006&from_month=ix". Retrieved 15 Oct 2014.

- ^ Yalom, Marilyn (2002). A History of the Wife. New York: Perennial. p. 188. ISBN0060931566.

- ^ DuBois, Ellen Carol; Dumenil, Lynn (2009). Through Women's Eyes : An American History with Documents (2d ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin'due south. p. 338. ISBN978-0312468873.

- ^ "12 Stats about Working Women". US Department of Labor. March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate - Men". FRED. January 1948. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Labor forcefulness characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2019 : BLS Reports: U.South. Bureau of Labor Statistics". www.bls.gov . Retrieved 2021-09-12 .

- ^ "Labor forcefulness characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2019 : BLS Reports: U.South. Bureau of Labor Statistics". world wide web.bls.gov . Retrieved 2021-09-12 .

- ^ Gemelas, Jordan; Davison, Jenna; Keltner, Case; Ing, Samantha (2022-02-01). "Inequities in Employment by Race, Ethnicity, and Sector During COVID-19". Periodical of Racial and Indigenous Wellness Disparities. 9 (1): 350–355. doi:x.1007/s40615-021-00963-3. ISSN 2196-8837. PMC7810107. PMID 33452573.

- ^ Noordt, Maaike van der; IJzelenberg, Helma; Droomers, Mariël; Proper, Karin I. (2014-x-01). "Wellness effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 71 (10): 730–736. doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101891. ISSN 1351-0711. PMID 24556535. S2CID 24523529.

- ^ Forchuk, Cheryl; Corring, Kevin Dickins and Deborah J. (2016-01-fourteen). "Social Determinants of Wellness: Housing and Income". Healthcare Quarterly. 18 (Special Issue): 27–31. doi:10.12927/hcq.2016.24479. PMID 26854545.

- ^ McWilliams, J. Michael; Meara, Ellen; Zaslavsky, Alan M.; Ayanian, John Z. (2007-12-26). "Wellness of Previously Uninsured Adults After Acquiring Medicare Coverage". JAMA. 298 (24): 2886–2894. doi:10.1001/jama.298.24.2886. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 18159058.

- ^ "She got a job at Starbucks for access to IVF treatment. It cost more her actual paycheck". NBC News . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ "Nonfatal Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses — United States, 2010". www.cdc.gov . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ "Educational Services, Health Intendance & Social Aid | Data USA". datausa.io . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ "Arts, Amusement & Recreation and Accommodation & Food Services | Data U.s.". datausa.io . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ "Transportation & Warehousing, and Utilities | Information USA". datausa.io . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ "Retail Merchandise | Data USA". datausa.io . Retrieved 2022-04-04 .

- ^ a b Gemelas, Jordan; Davison, Jenna; Keltner, Instance; Ing, Samantha (Feb 2022). "Inequities in Employment past Race, Ethnicity, and Sector During COVID-19". Journal of Racial and Ethnic Wellness Disparities. nine (one): 350–355. doi:ten.1007/s40615-021-00963-3. ISSN 2197-3792. PMC7810107. PMID 33452573.

- ^ Do, D. Phuong; Frank, Reanne (Dec 2021). "U.Due south. frontline workers and COVID-19 inequities". Preventive Medicine. 153: 106833. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106833. PMC8492358. PMID 34624386.

- ^ Pomeranz, Jennifer L.; Silver, Diana; Lieff, Sarah A.; Pagán, José A. (2022-02-09). "State Paid Sick Go out and Paid Sick-Exit Preemption Laws Across l U.S. States, 2009–2020". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi:ten.1016/j.amepre.2021.11.018. ISSN 0749-3797. S2CID 246763908.

- ^ "White Business firm Quango of Economic Advisors-The Long-Term Reject in Prime-Historic period Male Labor Strength Participation-June 2016-Page thirteen" (PDF). whitehouse.gov . Retrieved 4 Oct 2017 – via National Archives.

- ^ CEPR-Multiple Authors-Understanding the decline in the labour strength participation charge per unit in the United States-Baronial 2014

- ^ "Noncombatant Labor Force Participation Rate". FRED. January 1948. Retrieved February eighteen, 2018.

- ^ BLS-Howard Fullerton-Labor force participation: 75 years of modify, 1950–98 and 1998–2025-December 1999

- ^ Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System-The Recent Turn down in the Labor Forcefulness Participation Rate and Its Implications for Potential Labor Supply-See Effigy 3-2006

- ^ Peter Barth and Dennis Heffley "Taking Apart Taking Part: Local Labor Strength Participation Rates" Archived 2007-07-01 at the Wayback Auto University of Connecticut, 2004.

- ^ "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate Historic period 25-54". FRED. January 1948. Retrieved February eighteen, 2018.

- ^ Bloomberg-Jamrisko et. al-Yellen'due south Labor Market Dashboard-February 2, 2018

- ^ "Civilian Labor Force Participation Charge per unit - Men Aged 25-54". FRED. January 1955. Retrieved Feb 18, 2018.

- ^ "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate - Women Anile 25-54". FRED. January 1955. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h Morisi, Teresa (January 1, 2017). "Teen Labor Force Participation earlier and later the Not bad Recession and beyond". Monthly Labor Review. doi:10.21916/mlr.2017.5.

- ^ Richard Fry (April 11, 2016). "Millennials are the largest generation in the U.Southward. labor strength". Retrieved Apr 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "U.Southward. labor market place inches back from the COVID-xix shock, merely recovery is far from complete". Pew Inquiry Center . Retrieved 2021-09-12 .

- ^ "Task Openings and Labor Turnover Summary - 2021 M09 Results". www.bls.gov . Retrieved 2021-11-19 .

- ^ "Trends in Employee Resignation Rates: Picket Out for Summertime 2021". Visier Inc. 2021-06-04. Retrieved 2021-11-19 .

- ^ "Worker Shortage Crunch Intensifying as Chore Openings Rise Month over Month". www.uschamber.com . Retrieved 2021-11-19 .

- ^ Mirza, Roy Maurer and Beth (2021-09-12). "Deconstructing the Swell Resignation". SHRM . Retrieved 2021-11-19 .

- ^ "The Great Resignation: Why People Are Leaving Their Jobs In Growing Numbers : Consider This from NPR". NPR.org . Retrieved 2021-11-nineteen .

- ^ U.South. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1948-01-01). "Labor Forcefulness Participation Charge per unit - Women". FRED, Federal Reserve Depository financial institution of St. Louis . Retrieved 2021-xi-19 .

- ^ "Noncombatant Labor Strength: Strange Built-in". FRED. January 1955. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ "Noncombatant Labor Force Participation Charge per unit Strange Built-in". FRED. Jan 2007. Retrieved Feb 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h i Cordero-Guzman, Hector (May 2013). "Immigrant Labor and the U.Due south. Economy: A Profile". New Labor Forum. 22: 16–27. doi:10.1177/1095796013484009. S2CID 155852987.

- ^ a b c Donato, Katherine; Piya, Bhumika; Jacobs, Anna (September ane, 2014). "The Double Disadvantage Reconsidered: Gender, Immigration, Marital Status, and Global Labor Force Participation in the 21st Century". International Migration Review. 48: 335–364. doi:x.1111/imre.12142. S2CID 143713300.

- ^ CIA World Factbook-Country Comparison on Labor Forcefulness-Retrieved February 20, 2018

External links [edit]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics folio on the Labor Strength Participation Rate

What Is The Size Of The Labor Force?,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_force_in_the_United_States

Posted by: shoafauncaughbove.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Size Of The Labor Force?"

Post a Comment